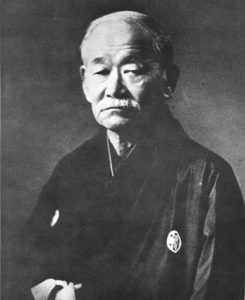

New Kanō Jigorō Memorial Sports Innovation Center Opening at International Pacific University IPU (April 2026), Okayama, Japan

(NOTE: Japanese below 日本語版は下記に添付)

On February 19, 2026, I interviewed Dr. Hisahi Sanada regarding the launch of the Kanō Jigorō Memorial Sports Innovation Center at International Pacific University (IPU) in Okayama, Japan.

The Center officially opens on April 1, 2026, at IPU’s Okayama Ekimae (Okayama Station) Global Campus.

Dr. Sanada, who joined IPU in April 2025 after retiring from a distinguished academic career at Tsukuba University will serve as the founding head of the Center.

What Is the Center Trying to Do?

In simple terms: take Kanō Shihan’s educational philosophy and apply it beyond judo.

Not just technically. Not just historically.

But structurally — into modern sport itself.

The long-term aim is the development of what Dr. Sanada describes as a “Sports-dō” model.

As judoka know, dō (道) is not merely technique. It is a Way — a lifelong path of cultivation extending beyond the dōjō into society and personal conduct.

The Center plans to explore how Kanō’s core principles might be applied to sports such as:

- Dance

- Volleyball

- Handball

- Swimming

⠀Not as branding exercises — but as philosophical re-grounding.

Because the Center is just opening, many of the concrete applications remain under discussion. What is clear, however, is the intention to examine how Kanō’s ideas might meaningfully inform contemporary sport.

Commentary: Why This Matters

Although the publicly disclosed plans are still developing, it will be especially interesting to see how the Center engages with Kanō Shihan’s central judo philosophies:

- Seiryoku Zen’yō — Maximum efficient use of energy

- Jita Kyōei — Mutual welfare and benefit

- Shūyō — Self-cultivation

- Jikō Kansei — Self-perfection

⠀Could this gradually evolve into a broader, Kanō-influenced Sports-dō Model focusing on:

- Moral and character formation

- Mutual development

- Lifelong educational trajectory

⠀This would stand in contrast to the largely Western-developed and globally adopted traditional sports model, which is typically:

- Performance-outcome focused

- Competitive metrics dominant

One can imagine future research asking questions such as:

What might volleyball look like if structured with judo’s cultivation ethic?

What if swimming incorporated explicit principles of mutual welfare?

How might dance training change if framed around disciplined self-perfection rather than performance metrics alone?

These are open questions — and perhaps that openness is part of what makes the project compelling.

This should prove very interesting to watch as the Center begins its ambitious work, and many of us will follow its development with real anticipation.

Practical Plans

The Center intends to:

- Recruit interested Japanese and international IPU students

- Introduce Center student volunteers to basic judo instruction in coordination with the Kōdōkan Instruction Department

- Conduct research into the writings and educational philosophy of Kanō shihan

- Explore practical sport applications of his philosophy

⠀IPU currently hosts approximately 320 international students from 19 countries, with strong representation from China, Vietnam and growing numbers from other nations. A number of short-term researchers from associated universities are active at IPU, and it plans to expand its current relationships with foreign universities. IPU also has a successful women’s judo program that has recently produced national champions in their divisions.

Dr. Sanada noted that institutional support for the Center developed quickly (less than 10 months, almost unheard of in Japan!), reflecting IPU leadership’s consensus view that Kanō’s educational model has relevance beyond judo — and potentially global relevance in modern sport.

Why Judoka Should Pay Attention

For decades, Kanō’s philosophy has been cited in speeches and ceremony — sometimes more as homage than as operational framework.

This Center appears to be attempting something more ambitious:

To operationalize Kanō’s principles beyond the tatami.

If successful, this could represent a meaningful evolution in how Japanese sport philosophy is presented internationally — not simply as martial heritage, but as an educational framework adaptable to contemporary global athletics.

For many years, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), under Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has dispatched judo instructors overseas, introducing judo as part of Japan’s cultural heritage.

Now, a private university is exploring whether the deeper dō dimension of judo can be made applicable to a much broader global sports audience.

It is an ambitious undertaking — one arguably aligned with Kanō Shihan’s original vision of judo as a vehicle for educational and social betterment.

We will watch closely.

Best wishes to Professor Sanada and the new Center!

Point of contact for any questions regarding the new Center is Assistant Professor Horikawa Takashi, PhD 堀川峻, Department of Physical Education, International Pacific University, Okayama, Japan.

~takashi.horikawa@ipu-japan.ac.jp~

(NOTE: Japanese below the admin blocks 日本語版は下記に添付 )

Lance Gatling ガトリング • ランス

The Kanō Chronicles© 2026

Tokyo

Enter your email below to get updates regarding new materials. We’ll never sell your information – in truth I wouldn’t know how if I wanted to do so.

2026年2月19日、私は岡山県に所在するインターナショナル・パシフィック大学(IPU)に新設される「嘉納治五郎記念スポーツ・イノベーション・センター」の設立について、真田久教授にインタビューを行いました。

同センターは、2026年4月1日にIPU岡山駅前グローバルキャンパスにて正式に開設されます。

真田教授は、筑波大学における長年にわたる卓越した学術キャリアを経て2025年4月にIPUへ着任し、本センターの初代センター長を務められます。

■ センターは何を目指しているのか?

簡潔に言えば、嘉納師範の教育理念を柔道の枠を超えて応用することです。

単に技術面においてではなく。

単に歴史的継承としてでもなく。

むしろ構造的に ― 現代スポーツそのものの中へと組み込むことです。

長期的な目標は、真田教授が「スポーツ道(Sports-dō)」モデルと呼ぶ枠組みの構築にあります。

柔道家であれば周知の通り、「道」は単なる技術ではありません。

それは道場を超え、社会や個人の在り方へと広がる、生涯にわたる修養の道です。

本センターでは、嘉納の中核原理を以下のような競技へ応用できないかを検討していく予定です。

ダンス

バレーボール

ハンドボール

水泳

これは単なるブランド拡張ではなく、哲学的基盤の再構築を意図するものです。

開設直後ということもあり、具体的応用については現在も検討段階にあります。しかし明確なのは、嘉納の思想が現代スポーツにどのように実質的影響を与え得るかを真摯に探究する姿勢です。

■ 論評:なぜ重要なのか

公表されている計画はまだ発展途上ですが、特に注目されるのは、嘉納師範の柔道哲学の中核概念とどのように向き合うかという点です。

精力善用 ― 最も効率的な力の活用

自他共栄 ― 相互の福祉と利益

修養 ― 人間形成

自己完成 ― 自己の完成

これらを基盤とした、より広範な「嘉納的スポーツ道モデル」へと発展する可能性はあるでしょうか。

たとえば:

道徳的・人格的形成

相互成長

生涯教育的軌道

これは、主として西洋で形成され世界的に普及した従来型スポーツモデルとは対照的です。従来モデルは一般に、

成果・結果重視

競技成績中心主義

という特徴を持っています。

今後の研究では、次のような問いが提起されるかもしれません。

柔道の修養倫理を基盤とした場合、バレーボールはどのように構造化され得るのか。

水泳に明示的な自他共栄の原理を組み込むとすれば何が変わるのか。

ダンスが単なるパフォーマンス指標ではなく、規律ある自己完成の枠組みで再定義されたらどうなるのか。

これらはまだ開かれた問いです。そして、その開放性こそが本プロジェクトの魅力の一部かもしれません。

センターの挑戦的な取り組みが始動する中、その展開を多くの関係者が大きな期待をもって見守ることになるでしょう。

■ 実務計画

センターは以下を予定しています。

日本人および留学生IPU学生の募集

講道館指導部と連携した学生ボランティアへの基礎柔道指導導入

嘉納師範の著作および教育思想の研究

その思想の実践的スポーツ応用の探究

IPUには現在、19か国から約320名の留学生が在籍しており、中国およびベトナムからの学生が多く、他国からの学生も増加しています。また、提携大学からの短期研究者も活動しており、今後さらに海外大学との関係拡大を予定しています。IPUは女子柔道においても強豪校として知られ、近年は各階級で全国優勝者を輩出しています。

真田教授によれば、本センター設立に向けた学内承認は非常に迅速に進み(日本ではほとんど例を見ない10か月未満での実現)、これは嘉納の教育モデルが柔道を超え、現代スポーツ全体、さらには国際的文脈においても意義を持つというIPU指導部の一致した見解を反映しているとのことです。

■ 柔道家が注目すべき理由

長年にわたり、嘉納の哲学は式典や挨拶の中で言及されてきましたが、しばしば理念的敬意の表明にとどまってきました。

本センターは、より野心的な試みに挑もうとしています。

すなわち、嘉納の原理を畳の外で実装することです。

もし成功すれば、日本のスポーツ哲学が国際的に提示される在り方において重要な進化となる可能性があります。武道の伝統としてではなく、現代グローバル競技に適応可能な教育的枠組みとして提示されるからです。

長年、日本国政府外務省所管の国際協力機構(JICA)は、柔道を日本文化の一環として海外に紹介するため、柔道指導者を派遣してきました。

現在、私立大学が柔道のより深い「道」の次元を、より広範な国際スポーツ社会へ応用できるかを模索しています。

これは野心的な試みであり、嘉納師範が当初構想した教育的・社会的向上のための柔道観と整合的なものとも言えるでしょう。

今後の展開を注視していきたいと思います。

真田教授ならびに新センターのご成功を心よりお祈りいたします。

本センターに関するお問い合わせ先:

堀川峻 准教授(PhD)

インターナショナル・パシフィック大学 体育学部

Email: takashi.horikawa@ipu-japan.ac.jp

Leave a comment