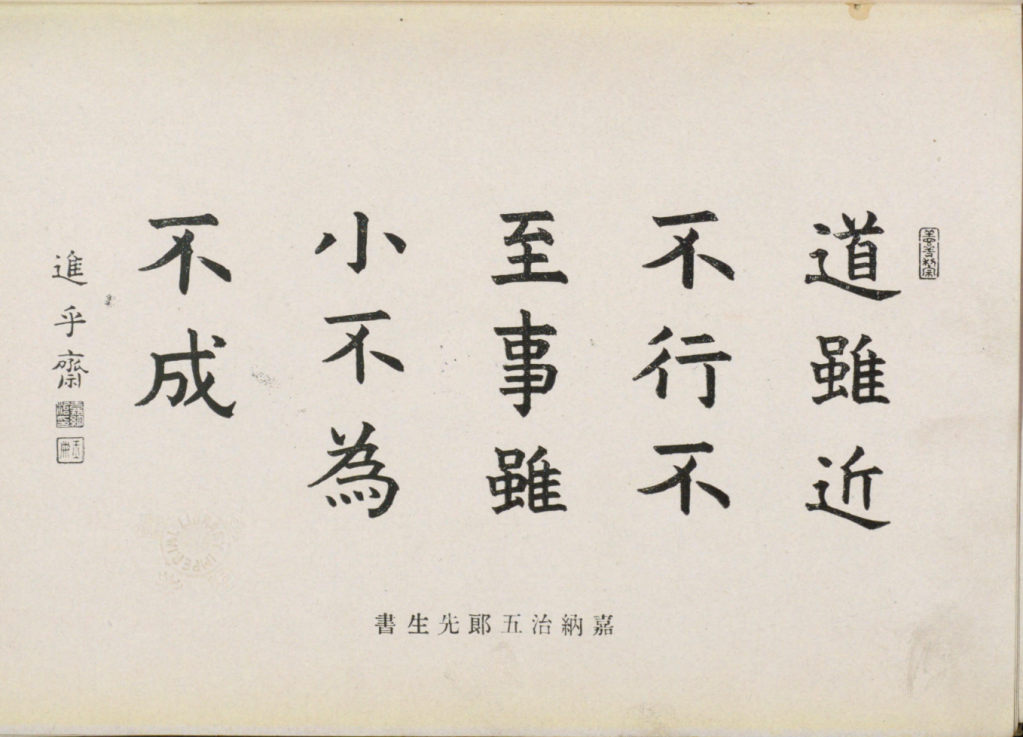

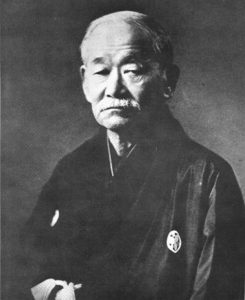

Kanō Jigorō’s calligraphies are well documented. He was fairly prolific, writing various sayings he adopted for jūdō instruction, usually in a very distinct hand with a block-type script.

Recently I found a heretofore a calligraphy unmentioned by Kanō scholars and archivists in an obscure book published in the 1920s. I found it interesting enough to research it a bit and translate it from the original Chinese over two millennia old.

While Kanō wrote top to bottom / right to left, the original text can be grouped left to right top to bottom as:

道雖近

不行不至

事雖小

不為不成

Even if the Way is near,

not going –

you cannot arrive;

even small matters,

not doing –

remain incomplete.

A possible alternate translation:

Although the Dào is near,

it cannot be traveled without traveling;

although a matter is small,

it cannot be done without doing.

My interpretation is that Kanō creates an admonition to action – to move, to do, to practice in pursuit of self-cultivation. Don’t just consider the Way, move yourself to travel it despite the hardships involved (the chapter cites many hardships).

The text is an extract from the writings of Xunzi 荀子 (JA: Junshi, 3rd century BCE), one of the most famous Confucian philosophers. The specific context is the book 脩身 Xiūshēn “Self Cultivation”, which emphasizes that a “gentleman” (i.e., a well-educated, moral, upstanding person) should act according to 礼 rei (CH: li).

“Wing-tsit Chan explains that 礼 rei / li originally meant “a religious sacrifice, but has come to mean ceremony, ritual, decorum, rules of propriety, good form, good custom, etc., and has even been equated with natural law.”[1] (English Wiki: “Li” Confucianism )

Xunzi 荀子 脩身 Xiūshēn “Self Cultivation”, Chapter 8 complete:

夫驥一日而千里,駑馬十駕,則亦及之矣。將以窮無窮,逐無極與?其折骨絕筋,終身不可以相及也。將有所止之,則千里雖遠,亦或遲、或速、或先、或後,胡為乎其不可以相及也!不識步道者,將以窮無窮,逐無極與?意亦有所止之與?夫「堅白」、「同異」、「有厚無厚」之察,非不察也,然而君子不辯,止之也。倚魁之行,非不難也,然而君子不行,止之也。故學曰遲。彼止而待我,我行而就之,則亦或遲、或速、或先、或後,胡為乎其不可以同至也!故蹞步而不休,跛鱉千里;累土而不輟,丘山崇成。厭其源,開其瀆,江河可竭。一進一退,一左一右,六驥不致。彼人之才性之相縣也,豈若跛鱉之與六驥足哉!然而跛鱉致之,六驥不致,是無它故焉,或為之,或不為爾!

道雖邇,不行不至;事雖小,不為不成。

其為人也多暇日者,其出入不遠矣。

In the middle of the text for Chapter 8, Xunzi cites the Dàoist binaries

「堅白」、「同異」and「有厚無厚」.

「堅白」Jiān bai – hard / white.

「同異」Tóng yì – Alike / unalike

「有厚無厚」Yǒu hòu wú hòu – Profound / superficial

Jiān bai hard / white is a strange couple, one that is not the normal statement of opposites (e.g., Yin / Yang, hot / cold, hard / soft). It is a couple used in earlier Mohist, Dàoist (including Zhuangzi) and even ancient School of Names texts to both introduce sophistry and to criticize sophists who would argue what is hardness, what is white? What is sameness and not sameness? But it apparently over the ages it eventually became a sort of shorthand for “Speaking directly and clearly / speaking to obfuscate” or wasting time and effort in sophistry.

Subscribe above with your email to get automatic updates of new material!

Comments welcome! See entry block at the end of Notes.

Notes:

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/xunzi/ accessed 2023/06/22

Xunzi 荀子 (third century BCE) was a Confucian philosopher, sometimes reckoned as the third of the three great classical Confucians (after Confucius and Mencius). For most of imperial Chinese history, however, Xunzi was a bête noire who was typically cited as an example of a Confucian who went astray by rejecting Mencian convictions. Only in the last few decades has Xunzi been widely recognized as one of China’s greatest thinkers.

While Xunzi is not included in the normal, basic Chinese classics education that Kanō began at 6 or 7 years of age, which focuses on the 四書五経 Shisho Gokyō The Four Books and the Five Classics, he later studied at what is today Nishogakusha University, at the time a juku private school focused on ancient Chinese texts. (The Five Classics: Book of Odes, Book of Documents, Book of Changes, Book of Rites, and the Spring and Autumn Annals. The Four Books: the Doctrine of the Mean, the Great Learning, Mencius, and the Analects, the core books of the Confucian canon.)

As always, I use the fabulous Chinese Text Project http://www.ctext.org to research the ancient texts. “The Chinese Text Project is an online open-access digital library that makes pre-modern Chinese texts available to readers and researchers all around the world. The site attempts to make use of the digital medium to explore new ways of interacting with these texts that are not possible in print. With over thirty thousand titles and more than five billion characters, the Chinese Text Project is also the largest database of pre-modern Chinese texts in existence.”

On this calligraphy, Kanō shihan’s pen name is written by the three small vertical characters on the far left of the scroll, 進乎斎 followed below by two seals stamped in black ink (this may be a black and white photo with the original seals in red, the normal convention).

「進乎斎」Shinkosai, used in this calligraphy, was Kanō’s pen name in his 60’s, namely 1920 to 1930. 進乎斎 Shinkosai is thought to be a reference to certain writings of 莊子 Zhūangzi (Chinese for “Master Zhūang”, Japanese: Sōshi), one of the most influential philosophers of the Dào (Chinese: Dào 道 , Japanese: Dō, often earlier in the West as Tao), “The Way”, active during China’s Warring States period [350 BC-250 BC]. Shinko 進乎 (progress) appears in two noted passages of his most important text, the Zhūangzi, one of the two foundational Daoist texts along with the Dào De Jing. The sai 斎 of Shinkosai is an old Japanese variant of the traditional Chinese character 齋 zhāi (simplified today as 斋) which means “to fast” or “study”, so Shinkosai means something like “progress through fasting”. In this sense “fasting” means the Dàoist discipline of focusing the spirit to learn the Way and the true nature of things by isolating the spirit from the distractions of perceptions of the physical world (represented by “hearing”), emotions and thought. (Handler S, 2022 communication).

The Zhūangzhi chapter thought to be the source of Kanō’s pen name is the 2500 year old Dàoist tale of a master butcher. Lord Wen-hui, captivated by the evident skill of the Butcher Ding (in some translations Ting), asked how Ding can so effortlessly butcher entire oxen.

Cook Ding replied that he only cared about the Way, which exceeded skill. But when he first began butchering oxen, all he could see was the ox. After three years he no longer saw the whole ox. Finally, he said, he proceeded by spirit alone and didn’t even look with his eyes. His skill was so effortless and insight so powerful that he never even had to sharpen his blade, using the same one for years, and the ox carcasses simply fell apart under his blade. Perception and understanding had stopped and he had proceeded to the point that his spirit moved where it wanted (Watson B, 2013), meaning it was in accordance with the Way of the Dao.

What I think Kanō meant by adopting such a pen name in his 60’s was that he was proclaiming he, too, had progressed beyond mere perception and thought and had learned to only seek the Way through his spirit. Even though Kanō paid tribute to Japanese tradition and nearly 2500 year old Dàoist thought by his choice of a pen name rooted in an ancient text, for Kanō the Way he sought to follow was not the Way of the Dào, but rather the Way of jūdō, which means “The Way of Flexibility.” Kanō defined that Way in part through the phrases 精力善用自他共栄 Seiryoku Zenyō Jita Kyōei, Best Use of Energy / Mutual Benefit, the modern jūdō philosophies he derived from the late 19th century writings of Herbert Spencer and other English Utilitarian philosophers he studied at the then new Tokyo University in his youth. (Gatling L, 2021)

Kanō was saying that he no longer needed perception of the physical world (hearing or seeing) or thought (knowledge or emotion) to employ the techniques that initially guided his pursuit of his Way, but now sought to proceed through the understanding and learning of his spirit alone. Having practiced for so many years, he could proceed simply by keeping his spirit focused on the Way. Without conscious thought he could accomplish the smaller things addressed by his perceptions and mind, honed by years of constant training and attentive practice of the Way of jūdō. He no longer saw people and situations, but looked beyond them to see the Way. In this he equated his understanding and skills with that of the estimable Butcher Ding.

This is not a surprise, given Kanō’s belief that dedicated study of jūdō could provide a level of 悟 satori enlightenment equal to that to be gained through intensely practicing 座禅 zazen seated Zen mediation for a decade or more. (Gatling L, 2022)

##

Discover more from The Kano Chronicles© 嘉納歴代©

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Hi, loved the information about Cook Ding.

LikeLike

it’s very famous among Confucianism fans. The lowly cook teaching the Duke.

LikeLike