This weekend I was mentioned by someone in a Judo Facebook group about an unattributed #blackbeltmagazine article citing the most influential women in judo that provided a list of those women and their accomplishments. I suspect being mentioned was to elicit a comment, and, being interested in the best history of judo, I bit.

I don’t read Black Belt magazine regularly but the clamor got me to read that article. Clearly the purpose if not the stated intent of it was to identify living female judoka who competed at the top tier of international competition for years and had an impact on what I call “sport judo”. In other words, today’s top winning competitive female sport judoka. But the first comment was a riposte of sorts to the original article, asking why wasn’t Fukuda Keiko sensei included in that list!?!

That seemed to be the sense of the majority of the posts thereafter – that any such list must include Fukuda Keiko!!! with lists of claims as to why she should be included.

One reason oft given claim is one that has always puzzled me:

• She was a direct student of Kanō shihan!!!

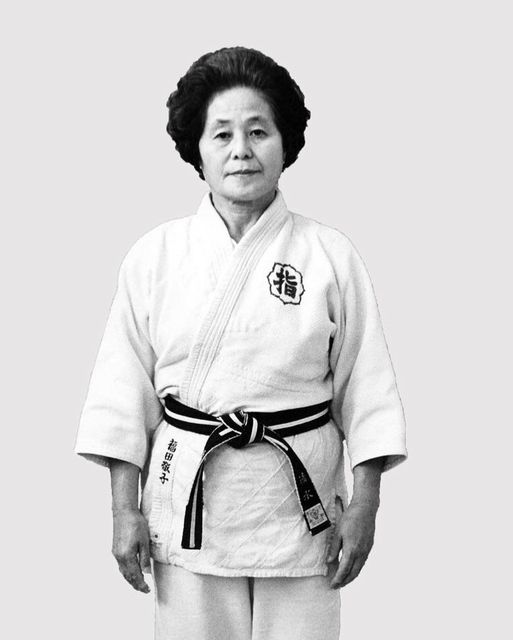

10th dan, USA Judo

and the United States Judo Federation (USJF) (2011)

wearing the red obi belt designating 9th or 10th dan grade

It’s an odd but precise construct that as far as I know has only one meaning in English, implying that she had some special teacher-student relationship with Kanō shihan. But I cannot find evidence of it.

While I’m not interested in post Occupation sport judo (particularly the arcane organizational mess that my fellow Americans have made of it) I do have a collection of 21 Japanese essays by Fukuda sensei written for Japanese audiences (I live in Tokyo and try to use only original Japanese sources for my research). After just scanning for 10-15 minutes I found one, written in 1985, in which she makes much of her jūdō education history explicit.

As background, Kanō shihan was very interested in women’s education and training, including physical education. But little was known in the 19th century or even the interwar years about the impact on the female body of hard physical training, continual impact from ukemi breakfalls, and in part because of that, Kanō, a man with five daughters of his own, took a very conservative yet innovative approach to women’s jūdō training. His solution was to develop a separate Kodokan Women’s Division program and hold all women’s training in a special, dedicated dōjō near his own office. One of the reasons for the later founding of the Association for the Scientific Studies on Judo was to promote medical research into the impact of potentially hazardous jūdō techniques like chokes and throws on young male bodies and, less obviously and unadvertised, female bodies. Access to that special dōjō was granted only with his personal confirmation, and he put his own then 41-year-old daughter, Watanuki Noriko, as the first director of the program overseeing its two senior, older professional male Kodokan jūdō instructors, Handa sensei and Uzawa sensei (see more about them below).

Instruction was initially solely provided by a number of senior male Kodokan instructors, supplemented by Watanuki sensei and later other female instructors as they matured through their own practice and promotions. The instruction was kata and randori training, with the instructors focused on their own specialty kata. Randori was only performed with other females. Kanō instituted the women’s obi belt, which had a white stripe overlaying the base colored belt, to signify that the women were separate. Kanō wrote that as women did not have the brute strength of men, they had to depend upon technique alone, which made their jūdō more pure.

Note white stripe 女子帯 female belt and

the kanji 指 shi, denoting 指導者 shidōsha instructor

set inside the outline of 八咫鏡 yatakagami,

the emblem of the Kodokan,

symbolic of an ancient, legendary spiritual mirror that reflects one’s soul

In her 1985 essay, Fukuda sensei wrote she joined the Suidobashi Kodokan as a student in the Women’s Division. This was in 1935 or 1936. (Also, it sometimes cited that Kanō shihan personally invited her or opened the Kodokan to women because of her. The latter claim is clearly not true. Regarding the former, I have been told by participants who trained under Fukuda sensei that she said Kanō shihan personally invited her to join the Kodokan; I find that entirely believable, as in his incessant proselytization of jūdō he invited untold numbers of young people to join, so certainly the young grandchild of his sensei would be offered the same!)

Fukuda sensei helped convince the Kodokan to make changes in that policy postwar.

Note the kagami mochi, the two stacked rice cakes on an offering stand,

a traditional Japanese New Year’s offering to the gods,

and the white stripe in the ladies’ obi.

The Kōdōkan 講道館 calligraphy (written right to left) brushed by Prince Katsu Kaishū, Kanō family friend, appears to be the large original that today hangs in the Kodokan Museum

She described traveling daily to the Kodokan from Noborito, a station south south east of Tokyo near Kawasaki, on the Odakyu Railroad (a one hour, one-way commute today, perhaps 90-120 minutes then?). The rail line was damaged in World War II air raids, so for some time during the war she stayed with the wife of a Kodokan instructor who lived closer.

In describing her Kodokan training in the women’s dōjō mentions several famous (and others not well known today) Kodokan instructors, some of whom she studied under, some she wished she had engaged earlier (as she and her sensei had all aged during her near 50 years of her Kodokan membership when she wrote the essay), but she wanted to remember and honor all her sensei, including,

– Nagaoka Shuichi 10th dan

– Kotani Sumiyuki 10th dan

She had “daily” instruction in the Women’s Division for years from

– Handa Yoshimarō, main instructor

– Uzawa Ariya, instructor

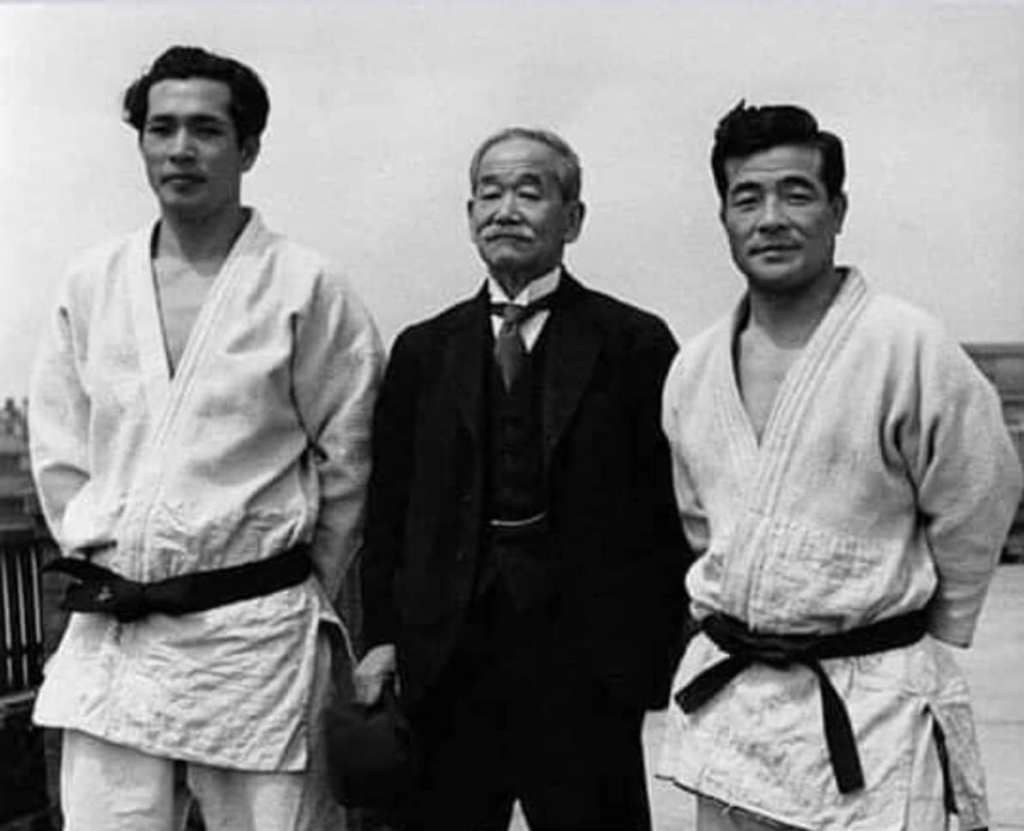

• Kanō shihan (seated center)

• Handa Yoshimarō sensei, its senior instructor (man to Kanō’s right)

• The man to Kanō’s left may be Uzawa Ariya, its other instructor (no evidence, just my guess!)

• Some believe the young woman over Handa sensei’s right shoulder is Fukuda Keiko, then 24 years old

• The original of the Kōdōkan 講道館 calligraphy (written right to left)

penned by Prince Katsu Kaishū, Kanō family friend, today hangs in the Kodokan Museum

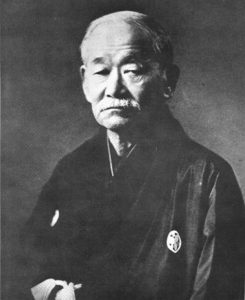

Note Kanō’s photo in formal Imperial court dress, complete with multiple Imperial awards and honors

Posthumously, he was awarded a high level of Japan’s Order of the Rising Sun

This is probably Kanō shihan’s last photo with the Kodokan female students

The late Prof. Kano’s ideal for women’s judo was to study randori in parallel with kata. This randori must be done between women. I was instructed only in this manner for the first ten years of my judo study. Judoists in general spend many hours on randori. Although it is also true in women’s judo, its characteristic is not to neglect kata while placing the importance on randori. This leads to the realistic methods of self-defense. This results in the increase of confidence in their everyday lives. Those who seriously study judo and master a higher degree of kata, may reach the point of acquiring “satori”, comparable to that concept of “spiritual enlightment” in Zen Buddhism, possessing a highly trained physique.*

Keiko Fukuda – Born for the Mat, a Kodokan Kata Textbook for Women, 1973

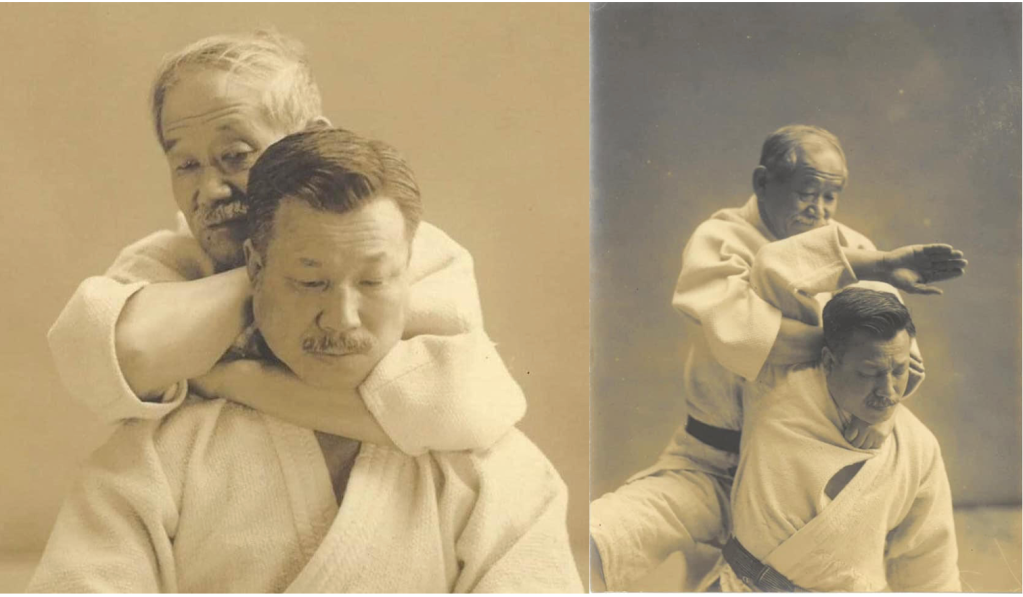

hadaka-jime (left: rear naked strangle) and

kataha-jime (single wing strangle)

These photos were apparently taken for Volume 2 of Kanō’s capstone jūdō book,

which, unfortunately, he never completed.

Handa became a Kanō favorite uke after the retirement of his lifelong partner Yamashita Yoshitsugu 10th dan (1865-1935). Perhaps writing of the very staged kata photos above (I think this likely as the dates roughly align), Fukuda sensei wrote that one day Handa sensei told her he had to pose for photos with Kanō shihan and seemed somewhat exasperated by the request, perhaps as he was then about 65 years old and the choking kata that Kanō demonstrated above are not at all pleasant for uke the person being choked (Kanō was about 75 years old; these are probably the very last photos of Kanō in his keikogi practice uniform, performing any sort of jūdō).

Postwar, Fukuda sensei’s “senpai” (senior) Noritomo Masako returned to practice, apparently after not attending for some time (perhaps because she fled Tokyo after the air raids began, as many other residents of the ravaged city did to avoid the death, destruction, and lack of food).

Fukuda sensei wrote of the impact of the WWII fire raid on the Kodokan, including her personally helping fight the fire with buckets of water, the relocation of the dōjō due to fire damage, etc.,

(See my description of the 1945 firebombing of the Kodokan here:

Kanō Chronicles: 1945 Firebombing of the Kodokan

I may rewrite it later to add Fukuda sensei’s account, the only firsthand account I know)

In the 1950s after things had settled down after the Occupation, she approached Mifune Kyuzō (later 10th dan) to teach Kodokan women the same techniques as men.

She mentioned Kanō shihan twice in this essay:

– He occasionally dropped by the Women’s Division dōjō, and she had the honor of having her practice being watched by him (written in a very specific Japanese idiom to make the honor implicit, but clearly her role was passive: she was being watched practicing, not interacting with Kanō shihan)

– He voiced the desire that judo be promulgated around the world

One would think if she had been “the direct student” of Kanō shihan, this was the time to point it out. But she did not. Her description was that of any other female Kodokan student of her day and situation, unremarkable from the standard program of a highly dedicated student. This is not a slight against Fukuda sensei – from my research, Kanō shihan simply didn’t ever teach much after his 20s, and from his 30s or so less and less all the time. Certainly into his 60s and 70s he didn’t teach much at all, if any. The professional instructors of the Kodokan attended daily, taught the students daily, and their descriptions of practice sometimes record the increasingly rare appearances, occasional comments, corrections and lectures by Kanō shihan.

But, as my judo bud Dr. Mike Callan, Professor, University of Hertfordshire points out, there are multiple ways to teach jūdō:

• kata

• randori

• mondō (question and answer)

• kyōgi (lecture)

If Fukuda sensei attended a particular Kanō lecture or participated in some particular class, she didn’t mention it here. But I’ll keep looking.

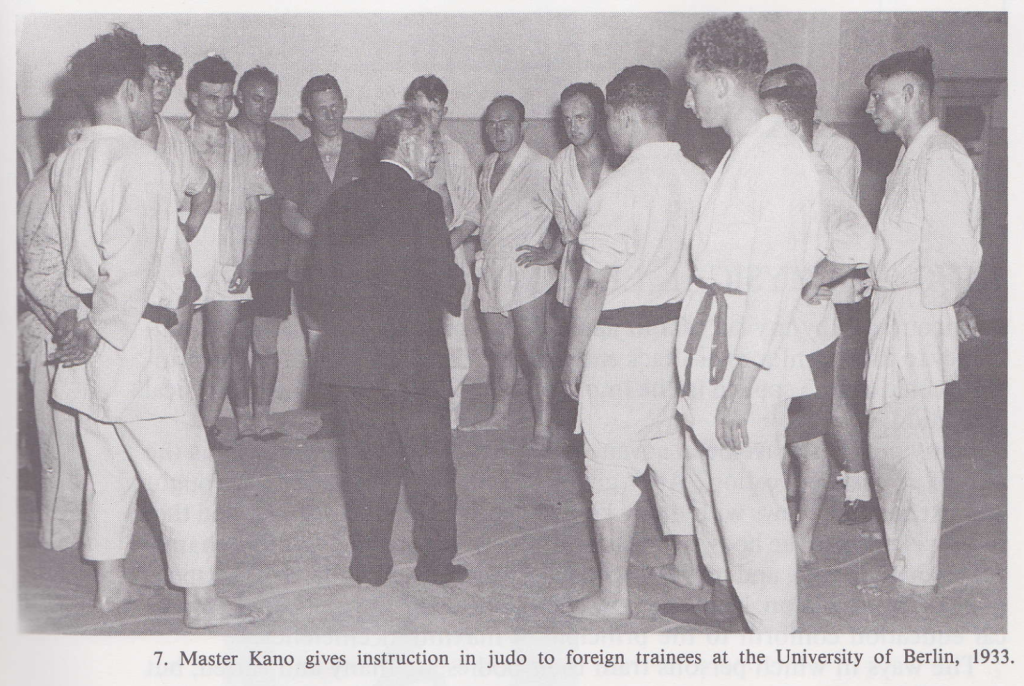

The photo below gives an idea of the scale of Kanō’s formal Kodokan lectures, hardly a special one on one event. But hard to forget.

I’ve never understood trying to gild this particular lily – Fukuda sensei devoted her life, effort and passion to judo, and that should be recognized, commemorated and celebrated, but I really doubt she was a “direct student” of Kanō shihan in any reasonable sense of the term.** She was a dedicated Kodokan student, and the instructors she named were exactly those that taught her and every other female student in the Kodokan Judo Institute of those days.

What is much more interesting to me is the series of international trips she took abroad to teach and proselytize judo before she settled down in America.

That would be interesting history.

NOTES:

* “Those who seriously study judo and master a higher degree of kata,

may reach the point of acquiring “satori“,

comparable to that concept of “spiritual enlightment” in Zen Buddhism,

possessing a highly trained physique.”

– Fukuda Keiko, Born for the Mat: A Kodokan Kata Textbook for Women, 1973

This quote is consistent with otherwise long forgotten comments by Kanō shihan 100 years ago in which he claimed that the embodiment of philosophy in jūdō is so enlightening that faithful, regular practice of its precepts in the dōjō and throughout life outside the dōjō would lead to the same ultimate level of enlightenment, satori, as practicing zazen seated Zen meditation for years cited in my long paper regarding the evolution of Kanō’s jūdō philosophies, an early version of which I presented to the American Philosophical Association in 2021 and can be read here: https://kanochronicles.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/gatling-apa-paper-2021-origins-of-the-principles-of-judo-final.pdf ).

In my experience, only a handful of Kodokan students knew of this concept

** Kanō shihan did have “direct students” but only noted when he was much younger; we know what that looked like. Outside of the Kodokan, in the late 1800s in self-designed experiments to test the abilities of female students, he taught his wife Sumako, some of her friends, and a couple of female cousins and nieces.

Kanō also in secret taught the very interesting Shimoda Utako, a pioneering female educator and long term colleague. Around 1891, Kanō and Shimoda were rumored to be linked romantically (in fact, in the most diplomatic terms possible, the young widow and proto-feminist Shimoda was rumored by political opponents to be particularly sexually promiscuous, accused of having slept with most key members of the conservative government, men with whom Kanō was closely aligned). Once a major newspaper reported that the two had married without notice – only to issue a retraction days later. (I cannot determine if the news was in error or if Kanō and Shimoda married then divorced.)

Given the nickname Utako “Poem Child” by the Meiji Empress, her poetry student

Famous as a pioneering female educator, feminist, and irascible free spirit

Widowed as a young woman, taught jūdō in secret by Kanō,

she was romantically linked to Kanō and remained a lifelong colleague

In fact, it was a student of Shimoda sensei that in 1906 taught jūdō to the first US Embassy Tokyo jūdō students (my dōjō carries on that 120 year old tradition: US Embassy Judo Club http://www.usejc.org, Facebook http://www.facebook.com/usejc ), one the daughter of a diplomat, and another the wife of then US Army Captain John “Blackjack” Pershing, the US Army military attache to Tokyo. Pershing was later General of the Armies and commander of the American Expeditionary Force during World War I.

Kanō became increasingly frail in his 70’s (1930-1938) as old age and decades of chronic diabetes took their toll. By 1936, when Fukuda Keiko entered the Kodokan, Kanō, suffering from advanced diabetes and only able to walk with difficulty, was hardly in physical condition to teach jūdō in any conventional sense. He was also incredibly busy with his duties as an influential Emperor-nominated, lifetime member of Japan’s House of Lords, and supporting Tokyo’s bid and preparation for the 1940 Olympics. By the 1930s his visits to the Kodokan were so sporadic that they were typically noted in the Kodokan Diary column in Judo magazine, indicating, at least to me, such visits were not at all regular events, much less daily.

he no longer took his shoes off even when he entered the tatami,

and always carried a cane or umbrella.

(Kanō was first hospitalized for diabetes-related leg circulation problems in his late 40s / early 1900s

so it is perhaps safe to assume his diabetes started at least in his 40s or earlier.)

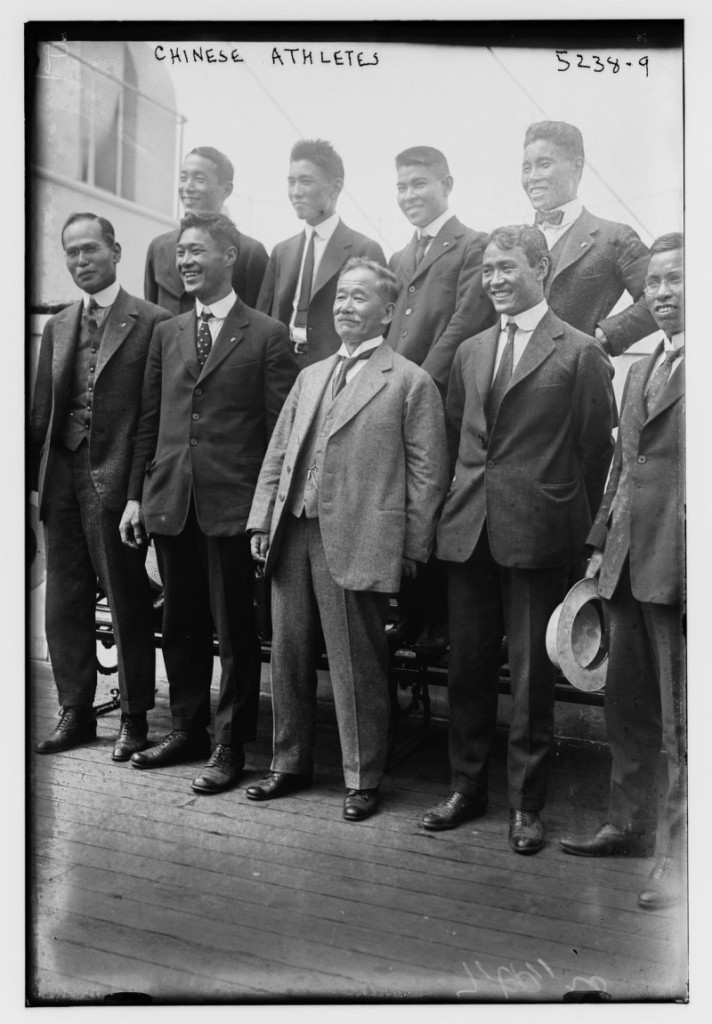

Note how he stands stiffly upright, his left arm held oddly behind himself,

most likely hiding his umbrella or cane to help him stand as he did for posed photos.

Unseen in the cropped photo is that he is standing on the mats with his shoes on.

in which Kanō played a key role as Chairman, Japan Amateur Athletic Association

Also, Kanō’s early 1900s Chinese student education program was famous in China

Note how his left arm conceals a cane or umbrella from the main camera behind him

The photo below was taken in Vancouver, Canada, April 1938, just hours before Kanō embarked upon the Japanese ultra-luxury NYK passenger liner Hikawa Maru bound for Yokohama, upon which he died days later of pneumonia, almost certainly brought on by his 40 year affliction with diabetes (which, if so, that ice cream cone certainly would have exacerbated).

In embarking on his last exhausting around the world trip in early February 1938, Kanō ignored advice from his doctor not to travel at all, and even refused to allow a traveling companion, thus traveling alone. One issei first generation Japanese immigrant to America who met him during the last weeks of that trip and personally spent days driving Kanō sightseeing and to various meetings wrote in a letter to Japan that he was enraged and embarrassed that his own people, the Japanese, would treat the aged, clearly ill, seriously weakened Kanō so callously as to send him around the world on a grueling months long trip alone, and was concerned the trip would kill him.

It did kill him.

Despite rumors that Kanō was poisoned by political enemies for his antiwar stance, his last days on the Hikawa Maru, the pride of the Japanese Pacific Ocean luxury fleet, are fairly well documented. He was the personal guest of the ship’s captain invited to dine at the prestigious captain’s table at every meal (most attendees rotate every meal through the elite of the passengers), a signal honor which placed him squarely in the public eye at least three times a day for the entire voyage; the captain was also later interviewed by the Japanese press about his VIP guest’s time on the ship and death. Also, a young Gaimusho Foreign Ministry diplomat returning to Japan on the same voyage observed, spoke with and dined with Kanō several times wrote of Kanō’s apparent illness, increasing frailty but continued characteristic stubbornness – Kanō insisted on dressing for every meal and joining the table of the captain, who time and again urged Kanō to remain in his cabin and rest instead, offering the ship’s crew and the steward to assist him and serve him any meals he wanted in the comfort of his cabin.

The morning of Wednesday, May 4, 1938, (local ship time: May 5 in Tokyo time, which is the date of death noted today) he died, attended by a steward and the ship’s medic, death confirmed by the captain. Cause: pneumonia.

The captain radioed the sad news to Tokyo:

Regretfully (he) entered eternal sleep this morning 6:33

When the Hikawa Maru arrived at Yokohama Friday, May 6, its normal quarantine was cut short and the ship was allowed to dock immediately.

The Emperor Hirohito dispatched the Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, his personal secretary, to meet the ship and escort Kanō to his home in his massive compound in Ōtsuka, Bunkyō-ku, his casket draped in the Olympic flag.

and escorted Kanō’s Olympic flag-draped casket in a long procession to his home in Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo

Days later Kanō’s formal Shintō funeral ceremony in the Kodokan drew over a thousand people,

including a large party of government representatives and a personal message from Emperor Hirohito

Today his cabin is marked with a brass plaque noting his name and the date of his death on the Hikawa Maru, which is on permanent display as a museum ship in Yokohama at Yamashita Park, near Yokohama Station.

It survived Kanō’s death, converted in 1941 to an Imperial Japanese Navy hospital ship

and painted white it moved 30,000 wounded troops and struck mines three times

Postwar she repatriated 20,000 Japanese soldiers stranded around the Pacific,

put back into commercial passenger service, then used as a youth hostel 1961-1971

Today, moored in Yokohama, it serves as a museum ship,

the only remaining Pacific luxury liner of that era

Sources: https://oceanlinersmagazine.com/2020/05/12/hikawa-maru-the-last-of-her-kind/

https://hikawamaru.nyk.com/history.html

##

Please type your email in the block below and hit Subscribe to be notified of new material.

– I have a number of new essays in draft and there may be something of interest among them. I guarantee they’re all unique, often topics never even discussed since the Occupation and the Kodokan began changing its history of wartime judo to stay on the good side of General MacArthur and General Headquarters (GHQ).

We don’t sell your data – we’re normally hard pressed to even find it.

Constructive comments are welcome – we read them all.

Criticism is fine but please cite resources if you think anything wrong or off base. I’m always happy to find new info.

– Most English resources don’t pass muster on most topics so don’t be surprised if I don’t agree with them.

– I have Japanese languages sources for everything herein except for Born for the Mat.

You can email me at Contact <AT> KanoChronicles.com

Lance Gatling ガトリング•ランス

Tokyo

##

Discover more from The Kano Chronicles© 嘉納歴代©

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Kick ass. This is good stuff.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for another beautiful article.

Best regards,

Milan Haška

LikeLike

Thank you. I’m glad you like it.

The great majority of this essay’s readers are in the US with a scattering of people around the globe.

Where are you? Are you the sole reader of this from Czechia?

If so, thank you.

LikeLike

Hello,

I am from Brno, which is a city in South Moravia in the Czech Republic. I am certainly not the only reader of your articles in the Czech Republic. I am looking forward to more articles.

With greetings and wishes for beautiful days,

Milan Haška

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now up to 7 readers in Czechia (which is how WordPress displays it)!!

Thank you again, watch for more…..

LikeLike

PS – please read it again – I added some other details perhaps of interest.

LikeLike

Hi Lance

It’s been awhile. Hope all has been well with you.

Since we last “talked” I’ve moved from California to Virginia.

My older brother, Fred, was in hospice here, so I came to take care of him for a few months before he passed. Then stayed to take care of probate and make arrangements with Arlington, as I promised him I would be sure he was honored at Arlington for his Silver Star.

[IMG_9821][IMG_1383][IMG_1385][IMG_2077]

I’m still waiting for a date, but he has been accepted to be buried in the ground with full Honors.

….

What a wonderful surprise to receive your latest update of The Kano Chronicles.

Wow! Totally enjoyed this latest article.

Smashing!!

And I appreciated the explanations of details within the photos. A wonderful collection indeed.

Your writing is as stimulating and interesting as always. I look forward to reading more future chapters.

Take care.

As always with love of old friendships of Fred and I.

Susan Chiaventone

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Thanks so much, Susan.

I’ll respond in detail via email.

My condolences for your brother. Thank you for your consideration of his service and wishes.

All the best,

Lance

LikeLike