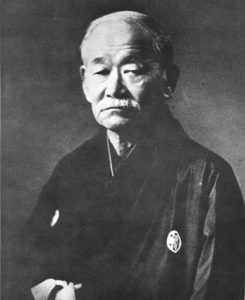

Kanō shihan wrote and lectured on the principle of 柔 jū, flexibility. He termed it as 柔の理 Jū no Ri, the Principle of Flexibility.

What is the origin of the term and its concept? What is the correct context?

The primary saying that is used to describe the core philosophy of jūjutsu is the four-character idiomatic Japanese phrase [1]

柔能制剛 Jū nō sei gō

Flexibility overcomes strength [2]

Or, more often cited in the West, but less correctly ‘Softness overcomes strength’ [3]

This saying is used to describe the core philosophy of jūjutsu – do not fight strength against strength, but rather deflect or avoid to neutralize the power thus wasted in attacking you.

But that is only the introductory line of the Upper Strategy, a portion of a much longer text. The complete primary text of the Upper Strategy of The Three Strategies of Huang Shingong (Chinese: 黃石公三略: Huang shigong sanlüe) from nearly 2250 years ago reads:

「軍識曰、柔能制剛、弱能制強。柔者徳也、剛者賊也。弱者人之所助、強者怨之所攻。 柔有所設、剛有所施、弱有所用、強有所加。兼此四者、而制其宣。」

Below is the first known complete English translation

(©2020 Lance Gatling, The Kanō Chronicles)

軍讖曰: The “Military Prophecies” cites:

柔能制剛 Flexibility controls the strong,

弱能制強 weakness controls strength.

柔者徳也 The flexible have virtues,

剛者賊也 the unyielding have faults.

弱者人之所助 The weak attract assistance,

強者怨之所攻 the strong attract opposition.

柔有所設 At times use flexibility,

剛有所施 at times use hardness,

弱有所用 at times use weakness,

強有所加 at times add strength.

兼此四者 One using all four

而制其冝 will then prevail. [4]

The primary purpose of the strategy was to cultivate effective interpersonal relations for leaders and rulers, how to deal with their own people. In the extended commentary it is clearly about dealing with subordinates first. The extension of the strategy since then was how to deal with non-subordinates, including enemies.

As one of China’s Seven Military Classics, this work has been studied for over 2000 years as one of China’s most important traditional schools of strategic thought.

Regarding its use in describing jūdō, apparently Kanō shihan thought it was insufficient to capture his vision; therefore, he developed his own explanation of the basic principles of jūdō that went through various versions, but eventually he settled on:

Seiryoku zen’yō Jita kyōei

This is typically translated into English as:

Best Use of Energy / Mutual Benefit

The origin of Kanō’s jūdō philosophies is complex, a tale that is explored in The Origins and Development of Kanō Jigorō’s Jūdō Philosophies by Lance Gatling, International Judo Federation Arts and Science of Judo , Vol. 1, No. 2, December 2021, pages 50-64, available at

Lance Gatling

Tokyo, Japan

info@kanochronicles.com

Endnotes:

[1] Japanese and Chinese use thousands of four character ideograms called yojijukugo in Japanese. These are used as in a wide array of situations from sayings to mnemonics to short hand for long stories or legends. Many are thousands of years old.

[2] 柔能制剛 Jū nō sei gō is Chinese. It is rendered in Japanese as 柔よく制剛 jū yoku sei gō the quality of flexibility / softness controls rigidity / hardness.

[3] The author contends that the typical translation of jū into English as ‘softness’ is neither correct nor appropriate in historical context and for the purposes of understanding jūjtsu or jūdō.

[4] “San Lüe 三略 (Three Strategies) is divided into three parts: Shang Lüe 上略, Zhong Lüe 中略, and Xia Lüe 下略. The first two parts quote from military writings of the past, Jun Chen 軍讖 (Military Prophecies) and Jun Shi 軍勢 (Military Power) and elaborates them, while the third part is the author’s own discussion. Some attribute the work to Huang Shigong 黃石公, but in recent research, it is said that this book was written by an anonymous person between the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) and Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD). “

From: The Governing Principles of Ancient China, Volume 2 – Based on 360 passages excerpted from the original compilation of Qunshu Zhiyao (The Compilation of Books and Writings on the Important Governing Principles), pg 508. Seri Kembangan, Malaysia: Chung Hua Cultural Education Centre, 2014.

Author note to FN 4: It is also entirely possible, indeed, perhaps likely that the Military Prophecies is in fact a fabrication added to imbue this work with more gravitas by “quoting” a much more ancient text than the newer work itself would import, as it seems there are no indications outside the Three Strategies that the Military Prophecies ever existed. Such a fabrication is not unknown in ancient Chinese texts (and those of other cultures).

Notes:

The entire work’s name in English is usually rendered as the The Three Strategies of Huang Shigong.

The Shang Lüe 上略, Zhong Lüe 中略, and Xia Lüe 下略 are respectively the Upper Strategy, the Middle Strategy, and the Lower Strategy.

The exact date of the Military Prophecies seems unknown but appears to be around 2400 years old.

English translation ©Copyright 2020, 2023 by Lance Gatling, The Kanō Chronicles

Lance Gatling

Author / Lecturer

The Kanō Chronicles

Tokyo, Japan

Contact@kanochronicles.com – please send a note to give us feedback.

Thank you!

Asian philosophy budo china Chinese philosophy Chinese students dojo dracula education history japan japan-times japanese history jigoro-kano jiujutsu judo judo jujutsu japanese history japan jujitsu kano kodokan budo bushido kano jigoro judo philosophy jujutsu Kano Jigoro keiko-fukuda Kobun Gakuin Kodokan Kodokan judo land use martial arts martial arts philosophy meiji japan history most valuable martial art philosophy principle of flexibility Seiryoku Zenyo Jita Kyoei Three Strategies tokyo womens-judo 三略 哲学 嘉納治五郎 柔の理 柔術 柔道 柔道哲学 武術 武道 講道館柔道 黃石公三略

The Kano Chronicles© 嘉納歴代©

The Untold History of Modern Japan and Japanese Martial Arts© 知らない近代日本史及武道史©