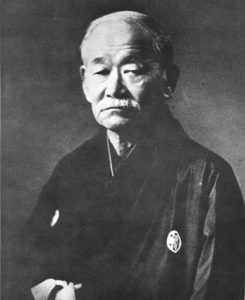

Tomiki Kenji 富木謙治 sensei (1900–1979)

a remarkable budōka, occupies a special place in the history of our US Embassy Jūdō and Jūjutsu Dōjō, Tokyo.

http://www.usejc.org http://www.facebook.com/usejc

(NOTE: the Tomiki essay translation starts at the end of this page.)

Background:

Tomiki sensei was born in 1900 in Akita Prefecture, where he began jūdō as a schoolboy. As a young man, he moved to Tokyo and continued his training at the Kodokan. In 1927 he graduated from Waseda University, Faculty of Political Science and Economics; around then, in his late twenties, he was introduced to Ueshiba Morihei, who at that time still used the name Ueshiba Moritaka, and began practicing aikibudō, as the precursor art to aikidō was known.

During the 1930s, the Imperial Kwantung Army (JA: Kantō Gun), the primary Japanese military force on the Asian continent, was being dramatically expanded. Originally a small garrison force of roughly 10,000–15,000 men, it reorganized as the Kwantung Army in 1919 and ballooned into Japan’s most prestigious army command. In the early 1930s it numbered 100,000–200,000 troops, but at its peak it reached 600,000–700,000 Japanese soldiers, supplemented by hundreds of thousands of less well-trained and poorly equipped Manchukuo forces.

General Tōjō Hideki, later the Prime Minister and son of Lieutenant General Tōjō Hidenori, Kanō shihan’s interlocutor in discussing physical education policy for the military and the Japanese people, served as Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army from 1934 to 1935, overseeing much of this buildup. The younger Tōjō was primarily a kendōka swordsman but had also trained in jūjutsu. Earlier, from 1928 to 1929, he had been assigned as Provost Marshal (Commander of the Kempeitai) of the Kwantung Army. As a result, he was familiar with hand-to-hand combat training at the Imperial Army Military Police School in Nakano, Tokyo. When the Kwantung Army later established its own Military Police school in Manchuria, perhaps senior Kempeitai graduates of the Imperial Military Police School in Nakano—where they trained under Ueshiba Morihei—tried to teach aikibudō. However, because Ueshiba’s teaching style was complex (some might call it unorganized or unrepeatable) and because he never seemed to produce or use formal lesson plans, it would have been difficult if not impossible to replicate.

Sometime in 1935, Tōjō personally invited (or so the story goes – I have no direct info to confirm this personal touch) Ueshiba Morihei (1883–1969) to move to Manchuria to teach his aikibudō martial art to the Kwantung Army Military Police, the Kempeitai.

Ueshiba declined the offer. By then he was in his early fifties and had previously seen combat as an infantryman in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) and attained the rank of corporal, which was a standard rank for superior performance during his term of service.

Ueshiba sought a suitable alternative instructor for the position; eventually Tomiki Kenji was offered and accepted a physical education / martial arts instructor position at the Kwantung Army Military Police school, moving to Manchuria in early 1936. In Shinkyo (today’s Changchung), Manchuria’s capital he taught the MPs, the Manchurian Capital Police, lectured and taught aikibudō at Daido University, and later became a professor at the newly founded Kenkoku University, Manchukuo’s national university. Tomiki, a jūdō 5th dan, was known to Kanō Jigorō shihan, who reportedly spoke to him before his departure for Manchuria about continuing his research into jūdō and hand-to-hand combat.

Why hand-to-hand combat training for the Military Police? In addition to normal gendarmerie duties like traffic control and handling deserters and disciplinary problems, some units performed what would come to be called “direct action missions”—intelligence gathering in contested or enemy-controlled areas, “snatch and grab” capture or kill of targeted individuals, or punitive raids against Chinese “bandits,” irregular or mercenary forces, often horse-mounted, ranging across Manchuria to operate against Japanese forces and settlements. Manchuria was a huge place, five times larger than Japan’s main island of Honshu, about the size of Germany plus France, and forces needed mobility, which meant incessant marching or training farm boys to ride horses.

And the Kempeitai used their training to brutal effect. One Japanese veteran spoke to the author about his service in a regular Kwantung Army infantry unit. In extended combat in Manchuria and China proper, he said the Chinese regulars and guerrillas were tough fighters; he and his comrades feared and respected them, and they all expected to fight them to the death; if captured, they fully expected to be executed out of hand. But he confided he was terrified of the Kempeitai—because if you were captured as a deserter or a bandit, “they would make you wish you were dead.”

Tomiki or someone else working with him eventually established a detailed, military-style aikibudō curriculum for the Kwantung Gun Kempeitai school; at least two versions of originals survived, one is held by Dr. Shishida Fumiaki, and another by the author. The latter version is apparently an approved final, as it is marked Top Secret – Not for Dissemination Outside! (the unit), which the draft version does not show. The curriculum is straightforward and familiar to me because of Nihon Jūjutsu (see below), with a limited version of modern Tomiki aikidō’s more complex taisabaki / unsoku (body movements / stepping movements) and a series of other techniques, complete with foot diagrams.

A contemporary account by a veteran member of the Kempeitai school training detachment described their budō 武道 martial arts training as follows:

horsemanship 馬術

rifle bayonet 銃剣術

jūdō 柔道

kendō 剣道

taijutsu 体術 (or variously aikidō 合気道, etc.)

hojōjutsu 捕縄術 (rope arresting techniques)

He describes the budō basic curriculum as:

– kendō without kata, focused on combat drills with wooden swords 木剣 and bamboo shinai 竹刀

– unlike jūdō, taijutsu starts with karatedō-like kicks and punches

—its main techniques were:

* 12 joint-lock techniques

* 5 striking techniques

* taught by a “70-something-year-old white-haired Ueshiba.”

The latter may simply be the impression of a young man encountering the prematurely gray-haired Ueshiba.

Hojōjutsu techniques were taught to every Kempeitai officer or trainee. For daily carry, veteran officers and trainees alike were issued a 5-meter-long, 6 mm diameter rope along with his whistle and notebook, but the veteran instructor noted that proper rope use was complicated and nearly impossible to remember even with practice.

Although he didn’t seem to talk about it directly after the war, despite being in his mid-40s, Tomiki—still in the inactive Army reserves because his regular military service had been delayed for years due to his student deferment and graduation from Waseda in his late twenties—was apparently called up and served in the Kwantung Army in its last-ditch defense against a massive Soviet invasion that destroyed it. After Japan’s defeat and surrender in August 1945, he was one of the estimated up to 600,000 Japanese taken prisoner by the Soviets; around one in ten died in the harsh conditions of the Siberian camps where he remained in captivity for almost four years (1945–1948). When he was finally released and allowed to return to Japan, he came back with little more than the clothes on his back.

My sensei, Satō Shizuya (1929–2011), was the son of a noted jūdōka who learned jūdō in the Imperial Navy and taught aboard a cruiser where he served in its engineering department; after completing his naval service, he became a jūdō instructor for the Tokyo Metropolitan Police. Satō sensei himself was an avid jūdōka; after middle school jūdō he entered the Kodokan in 1945. In 1949, after graduating from Meiji Gakuin’s Specialty (Business) School where his studies included English, he was hired into the Kodokan’s International Division, which at that time was learning how to deal with hundreds of Allied occupation troops who wanted to study jūdō and therefore needed English-speaking jūdōka. In an effort to minimize friction, without fanfare, the Kodokan established special classes for the Western Occupation troops separate from Japanese practitioners.

It was very popular; at its peak, that special class had nearly 400 students, primarily young and middle-aged military men assigned to the Occupation forces. My sensei was one of the instructors tasked with working with these men, and he formed friendships—budō friendships—that lasted a lifetime.

Satō sensei and Tomiki sensei met at the Kodokan, where the two practiced Tomiki sensei’s aikibudō, which he had continued to develop even while he was a prisoner in the Siberian work camps.

After two or three years of this, and after the Occupation ended in 1952, Tomiki sensei was engaged by the Kodokan to teach his martial art to US Strategic Air Command Security Police students in the SAC Combatives Course, along with jūdō and karatedō. Satō sensei acted as an assistant instructor and interpreter in what they renamed aikidō, alongside jūdō. Satō later adopted aikibudō into his practice in the US Embassy Dōjō in his own martial arts style, which he termed Nihon Jūjutsu (see http://www.nihonjujutsu.com).

During his nearly ten years in Manchuria before the Soviet invasion in August 1945, Tomiki sensei wrote a long and complex essay on his vision for the future of budō, aikibudō, and jūdō. Although it is not a priority for my current research, in honor of my sensei’s upcoming memorial day I intend to translate it, albeit piecemeal, so that I can eventually present the complete essay during my annual memorial visit to his grave in eastern Tokyo .

Without further introduction, here is the first installment of Tomiki sensei’s essay. As I’m not sure how WordPress handles piecemeal posts, I will just append to the end and put the latest addition notice at the top of this page.

****** Tomiki Kenji on the Future of Budō *****

Chapter 1 — Japanese Budō as the Way Leading to the Absolute

(Part 1)

Lance Gatling © 2026

The Japanese spirit is the driving resolve to realize the eternal and lofty great ideal of the imperial state. Japanese budō is the direct embodiment of that resolve, manifest both as power and as technique.

It holds within itself the willpower to press forward in spite of any obstacle. To examine the conditions through which such advance proceeds is the means by which the spirit of bu (martiality) is grasped; it is a spirit that prevails through ascent. Therefore, the spirit of martial arts is the spirit of victory—the spirit of superiority and excellence. Moreover, Japanese budō is the Way by which one triumphs over enemies, over nature, and over oneself, extending ultimately to the infinite and the absolute.

The Way that leads to the infinite absolute—the ideal of life—is not limited to the martial arts alone. It is found also in religion, in philosophy, and in the directions pursued by art and science. Religion has its own path; philosophy, art, and science likewise each have their own manner of proceeding.

Budō derives its distinctiveness from the disciplined practice and deep exploration of the arts of attack and defense. These arts of attack and defense constitute the absolute condition of budō: they signify the mental and physical attitudes and methods employed when one confronts “death” through an enemy’s attack in actual reality.

As mere techniques of attack and defense, such arts are not entirely absent from other so-called competitive disciplines outside budō. Nevertheless, when Japanese martial arts are considered from an embryonic and primitive perspective, they are rooted in fear in the face of “death”—that is, they are grounded in the instinct of self-preservation.

‘## To be continued in Chapter 1, Part 2

NOTES:

- In the US, the premier Nihon Jujutsu dōjō is the Japan Martial Arts Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan https://www.japanesemartialartscenter.com/

- You can find some indications of the younger Tomiki sensei’s thoughts on budō in his 1928 letter translated by Christopher Li of Aikido Sangenkai: https://www.aikidosangenkai.org/blog/a-letter-from-kenji-tomiki-to-isamu-takeshita/

- The Wiki entry for Tomiki Kenji is a huge mess – any number of purported facts are simply wrong, so use with caution.

- Sign up for notifications of further entries – enter your email and hit <Subscribe>

- See Feedback button below. I read them.

- Comment form enabled – be nice or be deleted. Facts I don’t know are welcome, and there is a lot I don’t know.

- A nice copyright free photo of Tomiki sensei would be most welcome!

2 responses to “Tomiki Kenji sensei on the future of budō”

-

Interesting … thank you!

LikeLike

-

Impressive English by Kanno sensei! He really learned it very well. Pronunciation spot on. Grammar nearly native, no obvious errors. Hilarious main point, come to Japan in person and see its glory for yourself. What a promoter! Thanks for sharing this.

/ Patricia Yarrow

LikeLike

Leave a comment